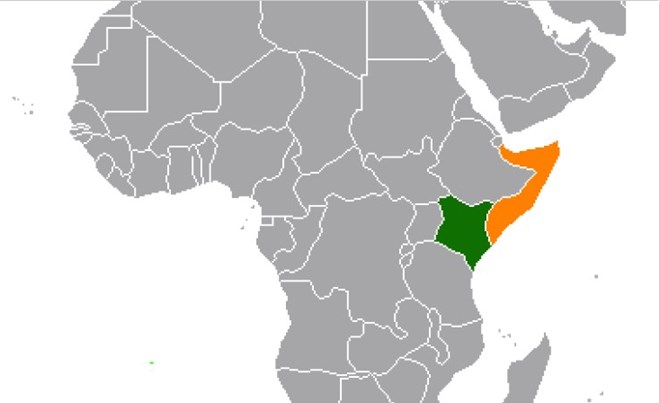

Kenya awaits hostile ruling in Somalia border row

Source: Nation, By Alex Ndegwa

Saturday September 25, 2021

Kenya is on high alert ahead of next month’s judgment on the Indian Ocean boundary dispute with Somalia, which is expected within government circles to be adverse.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) will announce the decision on October 12, ending a protracted case between the two neighbours that the war-torn Horn of Africa nation filed in 2014.

Its verdict is final. The timing of the judgment – it coincides with the 10th anniversary of Kenyan troops storming Somalia to fight the al-Shabaab terrorists – is also being considered a “slap in the face”.

advertisementsThe Nation has learnt Kenya will not accept a hostile ruling and a decision has been taken within the highest level of government to defy the court.

Disregarded

Some of the court’s verdicts have in the past been disregarded, including by the US, which in 2018 rejected the court’s order that sanctions against Iran should not include humanitarian aid or civil aviation safety.

And in 1986, the US had also attacked the court after it ruled America owed Nicaragua war reparations.

Kenya has also vowed not to accept what it considers “an illegitimate process” by an international entity.

“We are proceeding on the assumption that the verdict will be adverse. The manner in which the court conducted itself when dealing with Kenya, including rejecting a string of merited applications, is a key pointer,” a senior Kenyan official told Nation yesterday.

The official went on: “A lot is being done, including security-wise. It’s a matter with huge national security implications. A nation must guarantee the security and well being of its people.”

According to the official, even what would be considered a compromise by the court would involve surrender of a part of the territory, which is unacceptable to Kenya.

Treated unfairly

Kenya contends the court treated it unfairly by rejecting a string of merited applications, including one asking that judge Ahmed Yusuf, a Somali, should step down over conflict of interest.

Justice Yusuf had been at the helm of the court since 2018 and was replaced as president of the ICJ in February by judge Joan Donoghue from the United States.

Kenya has also alleged some world powers with interests in vast minerals within the contested area have been meddling with the case to ensure Somalia, which attempted to sell some oil blocks at an international auction in London, UK, takes over the area.

Nairobi boycotted the ICJ’s public hearings, leaving Somalia to argue its case in one-sided proceedings that closed in March in The Hague.

Bias

Judge Donoghue then announced that even without Kenya’s participation, the court would rely on previous documents filed by Kenya, which accuses the world court of bias.

Before Kenya notified the court of its withdrawal from the case on March 11, it had applied to be allowed to submit new evidence that has been “missing” and is “highly relevant”.

“Most particularly, the Republic of Somalia (“Somalia”), while asserting that its 1988 Maritime Law’s reference to a ‘straight line’ refers to an equidistance line, conveniently failed to produce the map included in the law,” Kenya stated in court papers filed in February.

“This Somali map, which the court should reasonably expect Somalia to produce, is critical since it has the potential of undermining Somalia’s entire claim … Whatever Somalia’s missing map depicts is categorically not an equidistant line.”

Kenya argued that any consideration of the equidistant claim would set a dangerous precedent as it would not only reward Somalia’s belligerent conduct but also had the potential of disturbing already established boundaries, triggering disputes including with neighbouring Tanzania that could escalate to South Africa.

The dispute

As adjacent coastal states facing the Indian Ocean to the east-south east, the maritime claims of Somalia and Kenya overlap, including in the area beyond 200 nautical miles.

The parties disagree about the location of the boundary in the area where their maritime entitlements overlap, according to court records.

Somalia, which filed the case in 2014, argues the maritime boundary between the parties in the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf should be determined in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) Articles 15, 74 and 83, respectively.

Article 15 of Unclos states: “Where the coasts of two states are opposite or adjacent to each other, neither of the two states is entitled, failing agreement between them to the contrary, to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two states is measured.”

But there is a rider. “The above provision does not apply, however, where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two states in a way which is at variance therewith.”

Article 74 states: “The delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between states with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.”

The same provision applies under Article 83 with respect to the delimitation of the continental shelf.

In both instances, the Articles provide where there is an agreement in force between the states concerned, questions relating to the delimitation of both the EEZ and continental shelf shall be determined in accordance with the provisions of that agreement.

Equidistance principle

Somalia’s argument is based on the use of the equidistance principle as the method of determining states’ maritime boundaries.

Accordingly, Somalia argues, in the territorial sea, the boundary should be a median line since there are no special circumstances that would justify departure from such a line.

With regard to the EEZ and continental shelf, Somalia contends, the boundary should be established according to the three step process that the court has consistently employed in its application of Articles 74 and 83.

But Kenya’s case is that a boundary along the parallel of latitude has developed through the consent of Somalia since 1979.

Since Somalia never protested for that long, Kenya contends that a boundary was established by a tacit agreement between the two states.

Straight line

Accordingly, Kenya’s position on the maritime boundary is that it should be a straight line emanating from the states’ land boundary terminus, and extending due east along the parallel of latitude on which the land boundary terminus sits, through the full extent of the territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf, including the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

Kenya measures the breadth of its territorial sea and EEZ from a series of straight baselines covering the full length of its coast.

These baselines were first declared in the 1972 Territorial Waters Act and have been amended from time to time.

Kenya’s submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) is that the outer limit of its continental shelf lies fully 350m from its coast.

Kenya asserts that all its activities including naval patrols, fishery, marine and scientific research as well as oil and gas exploration are within the maritime boundary established by Kenya and respected by both parties since 1979.

However, in 2014, shortly before filing its case with the ICJ, Somalia claimed a maritime boundary along an equidistance line, ignoring the 35-year recognition of the maritime boundary along a parallel of latitude.

Court decision

The court will determine, on the basis of international law, the complete course of the single maritime boundary dividing all the maritime areas appertaining to Somalia and to Kenya in the Indian Ocean, including in the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

Also, the ICJ judges will determine the precise geographical coordinates of the single maritime boundary in the Indian Ocean.

The judges are Yusuf, Peter Tomka (Slovakia), Ronny Abraham (France), Mohamed Bennouna (Morocco), Antônio Augusto (Brazil), Xue Hanqin (China), Julia Sebutinde (Uganda), Dalveer Bhandari (India), Patrick Robinson (Jamaica), James Crawford (Australia) Nawaf Salam (Lebanon), Iwasawa Yuji (Japan) and Georg Nolte (Germany).